3 Essential Design Patterns for Robust AWS Lambda Functions

When you first start with AWS Lambda, it’s easy to write simple, single-file scripts. But to build robust, enterprise-grade serverless applications, you need to apply proven software design patterns. These patterns help you create code that is testable, maintainable, and scalable.

This post will explore three essential design patterns—and their common anti-patterns—that will immediately elevate your Lambda functions.

Dependency Injection and the Principle of Separation of Concerns

Perhaps the most important principle for writing clean Lambda functions is Separation of Concerns. While not a formal design pattern itself, the principle is simple: always separate your core business logic from the Lambda handler code. The pattern we use to achieve this separation is Dependency Injection (DI).

The Anti-Pattern: Mixing Logic in the Handler

Developers often write all business logic directly inside the handler, creating the database client and mixing it with validation and event parsing. This makes the code impossible to test without creating complex mock AWS events.

Python

# ANTI-PATTERN EXAMPLE

import boto3

def lambda_handler(event, context):

# Dependency is created and used directly inside the handler

dynamodb_client = boto3.client('dynamodb')

# Business logic is mixed with event parsing

user_data = event['detail']

if not user_data.get("email"):

raise ValueError("Email is required.")

# Database interaction is hardcoded

dynamodb_client.put_item(

TableName='Users',

Item={'email': {'S': user_data['email']}}

)

return {"status": "User created"}

The Pattern: Inject Your Dependencies

You implement Separation of Concerns by designing your core logic functions to accept their dependencies (like a database client) as arguments. The Lambda handler is then only responsible for creating those dependencies and “injecting” them.

Python

# business_logic.py

# This function is pure, testable, and knows nothing about Lambda.

def process_user_signup(user_data: dict, db_client):

if not user_data.get("email"):

raise ValueError("Email is required.")

db_client.put_item(TableName='Users', Item=...)

return "User created"

# --- lambda_handler.py ---

import boto3

from business_logic import process_user_signup

# Initialize client once for reuse

dynamodb_client = boto3.client('dynamodb')

def lambda_handler(event, context):

user_data = event['detail']

# The dependency is "injected" into the core logic

result = process_user_signup(user_data, dynamodb_client)

return {"status": result}

With this pattern, you can easily unit-test process_user_signup by passing it a simple dictionary and a mock database client.

2. The Dispatcher Pattern for Routing Events

The Anti-Pattern: The if/elif/else Chain

A single Lambda is often triggered by different event variations from the same source (e.g., a DynamoDB Stream sends INSERT, MODIFY, and DELETE events). The most common anti-pattern is a long, cumbersome if/elif/else chain in the handler. This is hard to read and brittle to change.

Python

# ANTI-PATTERN EXAMPLE

def lambda_handler(event, context):

for record in event['Records']:

event_name = record['eventName']

if event_name == 'INSERT':

print("Handling INSERT event...")

# ... insert logic ...

elif event_name == 'MODIFY':

print("Handling MODIFY event...")

# ... modify logic ...

elif event_name == 'DELETE':

print("Handling DELETE event...")

# ... delete logic ...

else:

print("Warning: Unknown event type.")

The Pattern: Use a Dictionary as a Dispatcher

A cleaner approach is to use a dictionary as a “router” to map an event key to a specific handler function. This makes your handler readable and easy to extend.

Python

# event_handlers.py

def handle_insert(record): print("Handling INSERT event...")

def handle_modify(record): print("Handling MODIFY event...")

def handle_unknown(record): print("Warning: Unknown event type.")

# --- lambda_handler.py ---

from event_handlers import handle_insert, handle_modify, handle_unknown

EVENT_ROUTER = {

'INSERT': handle_insert,

'MODIFY': handle_modify,

}

def handle_records(records):

for record in records

event_name = record['eventName']

handler_func = EVENT_ROUTER.get(event_name, handle_unknown)

handler_func(record)

def lambda_handler(event, context):

handle_records(event['Records']

...

Adding support for DELETE events is now as simple as creating a handle_delete function and adding one line to the EVENT_ROUTER.

Expanding the Pattern: Handling Logical Outcomes

The dispatcher pattern isn’t limited to routing based on an event’s type. It’s an even more powerful tool for handling different outcomes from your business logic, such as success, validation errors, or downstream failures. This allows you to create clean, explicit paths for every possible result of an operation.

The Scenario: A Payment Processing Function

Let’s imagine a Lambda function that processes a payment. This single operation can have multiple distinct outcomes. A common but messy way to handle this is with a large if/elif/else block directly in the handler. This code can get hard to read and test because the business logic, error handling, and response formatting are all tightly coupled in one place.

Dispatching Based on Status

With the dispatcher pattern, we separate these concerns. The core logic function determines the outcome, and the handler dispatches that result to a dedicated function responsible for formatting the response.

Step 1: Define Outcome-Specific Handlers

First, create a separate handler for each possible outcome. Their only job is to create the final HTTP response.

# outcome_handlers.py

def handle_success(result: dict):

"""Handle successful payment."""

print(f"SUCCESS: Payment processed for transaction ID {result['transactionId']}.")

... # code for handling success outcome

return {"statusCode": 200, "body": "Payment successful"}

def handle_validation_error(error_message: str):

"""Handle validation error."""

print(f"VALIDATION_ERROR: {error_message}")

... # code for handling success outcome

return {"statusCode": 400, "body": error_message}

def handle_gateway_error(error_details: str):

"""Handle Gateway Error"""

... # code for handling error

return {"statusCode": 502, "body": "Payment provider error"}

# The router maps an outcome status to a handler function

STATUS_ROUTER = {

'SUCCESS': handle_success,

'VALIDATION_ERROR': handle_validation_error,

'GATEWAY_ERROR': handle_gateway_error,

}

Step 2: Define the Core Logic and the Dispatcher Handler

Next, the process_payment function contains the business rules and uses early returns to exit as soon as a rule fails. The main lambda_handler calls this function and uses the STATUS_ROUTER to dispatch the result.

# lambda_handler.py

import json

from outcome_handlers import STATUS_ROUTER

def process_payment(request_body: dict) -> tuple[str, dict | str]:

"""

Core business logic that returns a status and a result.

It uses early returns to handle failures.

"""

amount = request_body.get('amount')

# Rule 1: Validate amount exists and is positive

if not amount or not isinstance(amount, (int, float)) or amount <= 0:

return ('VALIDATION_ERROR', "Amount must be a positive number.")

card_token = request_body.get('card_token')

# Rule 2: Validate card token exists

if not card_token:

return ('VALIDATION_ERROR', "Card token is required.")

# --- All validation passed, proceed to core action ---

print(f"Charging payment gateway ${amount}...")

success = payment_gateway.charge(amount, card_token)

if not success:

return ('GATEWAY_ERROR', '...')

return ('SUCCESS', {'transactionId': 'txn_12345'})

def lambda_handler(event, context):

"""

Main handler that dispatches work based on the outcome of the payment processing.

"""

body = json.loads(event.get('body', '{}'))

status, result = process_payment(body)

handler_func = STATUS_ROUTER.get(status)

return handler_func(result)

Why This is Better

This design is better as it provides clear separation of concerns:

- Business Logic (

process_payment): Knows how to validate and process a payment. It knows nothing about HTTP status codes or JSON response bodies. - Response Formatting (

handle_*functions): Know how to create specific HTTP responses for different outcomes. They know nothing about business logic. - Orchestration (

lambda_handler): Knows how to connect the two. Its only job is to call the logic and dispatch the result.

3. Repository and DTOs for Consistent Data Handling

The Anti-Pattern: Inconsistent Payloads and Duplicated Queries

In a serverless system, lambdas communicate via message queues and shared databases. This can lead to data inconsistencies if not managed properly. This pattern uses two techniques to enforce data contracts: one for data moving between services (in-flight) and one for data in your database (at-rest).

Use Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) for Message Payloads

The Problem: JSON payloads sent between Lambdas have no enforced structure. If a producer Lambda changes a key name (userId to user_id), the consumer Lambda breaks at runtime.

The Solution: Define a strict contract using a Data Transfer Object (DTO), implemented as a Python dataclass. This DTO lives in a shared library or Lambda Layer.

- Producer: Creates a DTO instance and serializes it to JSON.

- Consumer: Deserializes the JSON back into a DTO instance. This fails immediately if the structure is wrong.

- Note: There can be multiple consumer and producer

Python

# shared/contracts.py

from dataclasses import dataclass, asdict

import json

@dataclass

class UserSignupDTO:

user_id: str

email_address: str

def to_json(self): return json.dumps(asdict(self))

@classmethod

def from_json(cls, s: str): return cls(**json.loads(s))

# In the consumer Lambda:

# payload = UserSignupDTO.from_json(record['body'])

# print(f"Processing user: {payload.email_address}")

This approach prevents runtime errors from data mismatches, acts as self-documentation, and enables IDE autocompletion.

Use the Repository Pattern for Database Access

The Problem: If multiple Lambdas access the same database table, you get duplicated query logic (e.g., the same boto3 call in five functions). Changing the query means updating it everywhere.

The Solution: Use the Repository Pattern. Create a single class (e.g., UserRepository) that contains all database access logic for that entity.

- All database queries for a specific table are methods within this single class.

- Lambdas call methods on the repository object instead of writing raw queries.

Python

# shared/database.py

import boto3

class UserRepository:

def __init__(

self,

table_name="Users",

ddb=boto3.resource('dynamodb')

):

self.table = ddb.Table(table_name)

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str):

response = self.table.get_item(Key={'userId': user_id})

return response.get('Item')

# In any Lambda function:

# user_repo = UserRepository()

# user = user_repo.get_by_id("user-123")

This keeps your code DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself), makes maintenance easy (change logic in one place), and abstracts the database details from your business logic.

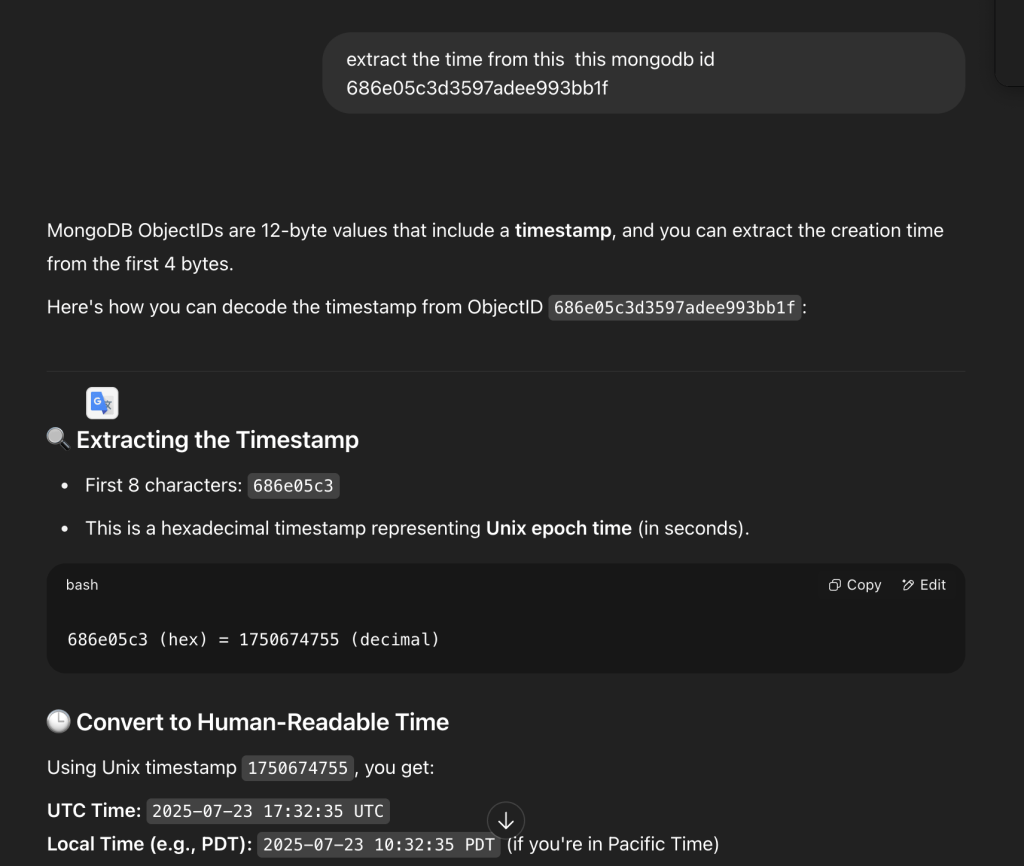

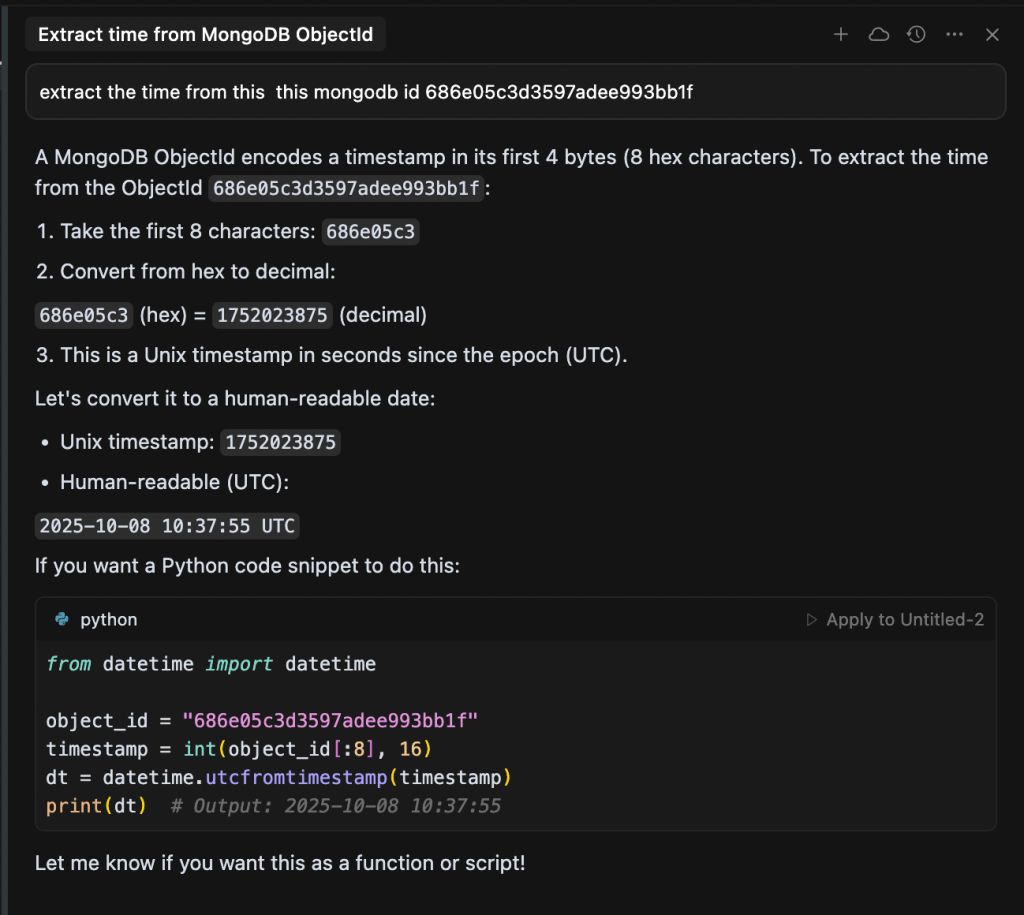

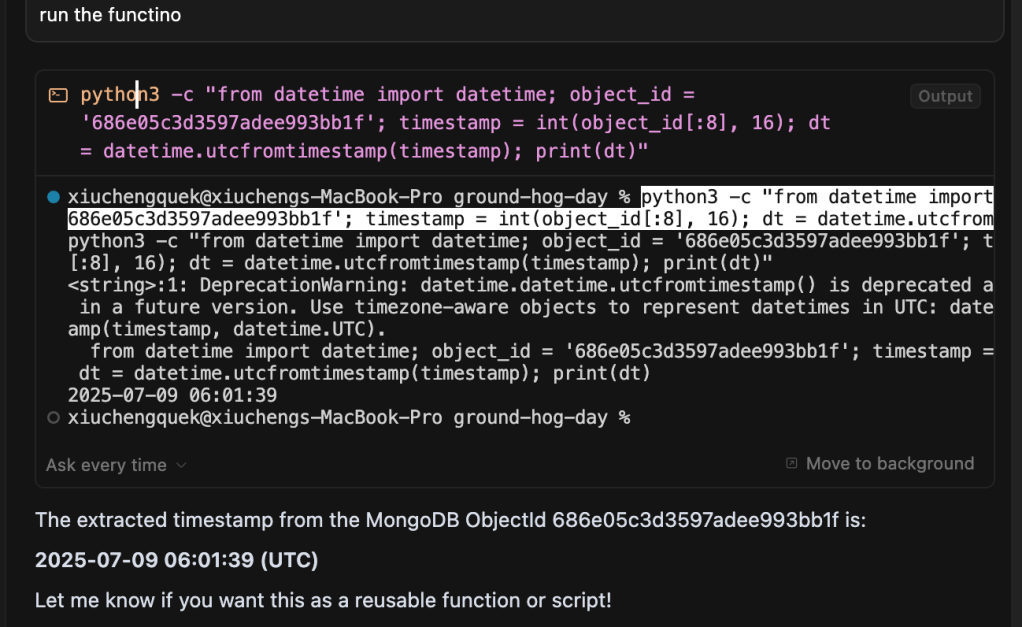

Design Pattern Provides A Blueprint For AI

The great news is that we live in the age of Large Language Models (LLMs). These models understand design patterns and now that you understand why these patterns are important, you don’t have to implement them from scratch. You can use clever prompting to have an AI partner do the heavy lifting.

More importantly, this method also prevents “AI code drift.” By consistently instructing an AI to use a specific pattern for a task—like always using the Repository Pattern for database access—you enforce architectural standards across your codebase. This ensures the code remains predictable and maintainable as the project evolves, regardless of who (or which agent/model) writes the prompt.

Therefore, instead of asking “write me a lambda,” you can now ask:

Prompt for DI: “Refactor this Python Lambda handler that uses dependency injection. Separate the core business logic from the handler and make the DynamoDB client an injectable dependency.”

Prompt for Dispatcher: “Write a Python Lambda handler that uses the dispatcher pattern to process DynamoDB Stream events. It should have separate functions for ‘INSERT’ and ‘MODIFY’ events and use a dictionary to route them.”

Prompt for Repository/DTO: “Generate a Python

UserRepositoryclass that uses Boto3 to interact with a DynamoDB table named ‘Users’. Also, create aUserDTOdataclass to represent the user payload.”

Ultimately, understanding design patterns lets you write better prompts and critically evaluate the AI-generated code, making the AI a more effective tool.